To Solve the Problem, Understand the Equation

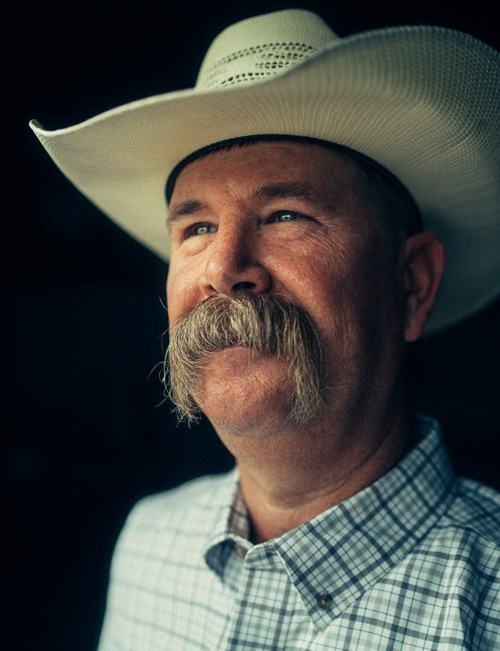

Aron Balok and the Roswell Artesian Basin

Jul / 2024

When he gets behind the wheel, the dusty flatlands of Eastern New Mexico stretching out before him, Aron Balok gets to thinking. “Windshield time,” he calls it

He might think about the cattle ranch where he grew up, about 60 miles south of Gallup, where he learned to appreciate the good years, when the rains came. Years when the cows were fat and the grass grew tall enough to stain his boots in the stirrups.

But more often than not, he is thinking ahead — planning for the worsening drought conditions predicted by climate experts and wondering what the future will hold.

Balok is the superintendent of the Pecos Valley Artesian Conservancy District (PVACD) – which is a fancy way of saying he helps manage the use of a vast basin of groundwater beneath the soil of southeastern New Mexico. The Pecos Valley is groundwater-reliant and heavily agricultural, dotted with ranches, pecan and fruit orchards, and farms. Balok understands what’s at stake — and how important it is to make that water last.

A Conservation Heritage

The Pecos Valley Artesian Conservancy District was formed in 1932. By the mid-1950s, aquifer levels were falling fast. The district had over 150,000 irrigated acres. Water use was unmonitored and unregulated. That’s when district officials took action, implementing, over the course of decades, a series of forward-thinking — albeit sometimes controversial — policies that have stood the test of time and positioned PVACD to handle the impacts of climate change better than most.

The groundwater Balok and the team manage is what’s known as a confined aquifer. In some ways that makes it the perfect testing ground for understanding the policies PVACD’s leaders and board members have implemented over the years. It’s relatively straightforward to measure fluctuations in this particular aquifer’s water levels — and to know how rainfall and the rate of human use is impacting those levels.

Understanding water in and water out is central to many of the policies PVACD has implemented over the years. After all, Balok asks, “How can you start to solve the problem if you don’t understand the equation?”

Here’s what they did:

- In conjunction with the State Engineer, they measured water use in the district and used those measurements to help define users’ water rights.

- Then they pulled nearly 20,000 acres out of production over the course of 20 years.

- They metered every well and capped agricultural use at 3 acre-feet per acre per year. (That’s about three swimming pools full of water.) “You can’t manage what you don’t measure,” Balok says.

- District officials initiated a low-interest loan program that helps fund improvements — ditch lining, field leveling, installation of more water-wise irrigation systems.

What's Ahead

“We are constantly bombarded with, ‘The end is near.’ That within the next 50 years, we’re going to be looking at 25 percent less water,” Balok says. “And if that happens, it can’t be understated. But it’s not hopeless. I think we as a society are going to have to decide what’s important to us.”

Balok and his team continue to focus on conservation. In a controversial move, they sometimes buy up water rights and hold onto them instead of reselling them to new users.

“I don’t know how you can reduce every farm by 25 percent,” he says, referencing that 50-year prediction. “That’s not something anyone’s going to be interested in. So that means you’re going to have to reduce acreage by 25 percent.”

Taken together, PVACD’s policies have set the district on a path of sustainability, Balok says — especially given the statewide policies already in place.

New Mexico follows the doctrine of prior appropriation — that is, the rule that gives the oldest water-rights holders seniority. That somewhat simple rule, Balok says, lays a strong foundation for water districts statewide. And in recent years PVACD has used it creatively to reduce water use by reducing acerage.

“We’ve got a really good system in New Mexico,” he says. “It’s one of my biggest frustrations that we get a bunch of well-meaning individuals together to discuss water policy, and we all feverishly set to work to invent the wheel. We’ve got one. We just need to use it.”

During his “windshield time,” Balok has found himself thinking a lot about what to do in the future if New Mexico’s multi-decade drought dissipates or climate predictions prove darker than reality.

He envisions a time when, thanks to PVACD’s forethought, the district has amassed enough water rights to consider doling them out again. If that happens, it will validate PVACD’s years of conservation planning. And according to Balok, that possibility is not so far-fetched.

“If we learn from our mistakes and learn from our successes, there’s certainly a pathway forward,” he says. “It might be difficult, but it’s not impossible. It’s within the realm of possibility.”

That learning process is well underway in New Mexico. And with the passage of the Water Security Planning Act of 2023, policymakers are engaging New Mexico residents in the planning. To get involved, visit mainstreamnm.org/get-involved.